The traumatic events that led John Mabry to seek refuge in opioids and alcohol might have kept many people buried under their oppressive weight for a lifetime. But instead, Mabry, who gained notoriety as an actor and stuntman in Hollywood, overcame those addictions to become a powerful voice in helping to combat the opioid epidemic, which was recently declared a national emergency in the United States.

Mabry’s experience in Toastmasters also is characterized by similar amounts of perseverance and courage, as he transcended a daunting fear of public speaking and two failed attempts to join Toastmasters clubs to become the accomplished and sought-after speaker that he is today.

“There was a time I couldn’t even stand in front of a mirror and speak to myself in a confident way,” says the 40-year-old. “Now I speak to groups of thousands with little trepidation.”

Mabry was a senior at Baylor University in Texas and starting a promising career in the performance arts when he experienced what he calls “seven seconds that changed my life.” While he was traveling on a highway near Houston, a tire blowout sent his car rolling more than 10 times, killing one of Mabry’s close friends and crushing both of Mabry’s legs. His right leg was eventually amputated below the knee as a result of the injuries and fitted with a prosthesis.

Mabry struggled with addiction, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for more than a decade following the accident. During that period he moved to San Diego to work on a master’s degree but found himself isolated from friends and family. “I was taking painkillers and drinking alcohol to handle the lingering terror of the situation,” Mabry says. “It was traumatic to constantly replay the sounds of the crashing and flipping and glass shattering from the accident. I never grieved the situation the way I should have and turned to substance abuse to cope instead.”

Mabry moved on to find success in Hollywood, working as an actor and stuntman. He appeared in popular American TV series like NCIS, ER and Cold Case, as well as in a number of movies, including Superbad and Sublime. Sometimes he portrayed characters who were amputees, other times he worked as an amputee body and stunt double for actors. He also served as a technical advisor for shows that involved amputee characters.

“I believe that the stigma associated with addiction kills more people than the drugs themselves.”

— JOHN MABRYHowever, his situation worsened when he found his brother dead from an accidental overdose in his Beverly Hills home. Despondent in the aftermath of that tragedy, Mabry had difficulty keeping work and was fired from a job with noted radio and TV personal-finance guru Dave Ramsey as a result of his addictions.

“I went from attending parties at the Playboy Mansion to living in a dilapidated trailer on the side of a river in Tennessee,” Mabry says.

The Journey Back

Approaching bottom, Mabry finally received the help he needed. He spent the next several years in seven different rehabilitation programs and eventually tamed his powerful addictions. Mabry now works as director of public outreach for Addiction Campuses in Nashville, Tennessee, an organization that provides comprehensive drug and alcohol addiction treatment programs throughout the U.S. Along the way Mabry also joined the Franklin Toastmasters club near Nashville, confronting his fear of speaking publicly about his personal struggles with addiction and emerging as a respected spokesperson in the fight against the opioid epidemic in America.

U.S. President Donald Trump declared that epidemic a national emergency in August of this year, a status that allows the executive branch to increase funding for expanding treatment facilities and to take other significant steps to fight the epidemic. Opioid overdoses now kill 91 people a day in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and nearly 35,000 people across America died of opioid or heroin overdoses in 2015, according to data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The World Health Organization estimates that 13.5 million people around the world take opioids, including 9.2 million who use heroin.

With his highly personal speech on the subject, titled “The Hero-In Solution,” Mabry won his division’s International Speech Contest this year. In it he stresses that moving addiction issues out of the shadows and into the light is a key to resolving the crisis. Addiction is a disease and it should be viewed that way, he says.

“I believe that the stigma associated with addiction kills more people than the drugs themselves,” Mabry says. “I want to help serve as a bridge from where people are now with substance abuse issues to where we need to be as a society. … Moving past the shame of addiction and talking more openly about it is essential to saving lives.”

He believes his brother’s overdose death is a tragic example of what can happen when addiction issues aren’t dealt with openly. “He didn’t share his problem with others and we didn’t want people knowing about his addiction, so he didn’t get the help he needed,” Mabry says.

Mabry’s own experience and professional knowledge of addiction lead him to believe many substance abuse issues result from deeply rooted problems. “It took me multiple stints in rehab to realize that some of my traumas had nothing to do with substance abuse,” he says. “They had to do with earlier feelings in life about not fitting in, feeling defective in some way, partially as a result of ear-related surgeries I had as a child.

“I had a lot of fear and anxiety under the surface that no one ever truly picked up on, including me.”

Persevering in Public Speaking

During an exit interview following the completion of his master’s degree, Mabry received what he now considers prescient advice from two of his professors: Consider joining Toastmasters. “They believed I had potential and some good things going for me, but they didn’t think I was where I needed to be as a public speaker,” Mabry says.

Mabry followed through on the suggestion but found his initial experiences with Toastmasters daunting. “I went to my first meeting and immediately quit,” he says. “I was trying to put myself out there and be naked with my emotions, but I wasn’t yet able to be present in that way in front of a crowd. I couldn’t be in my own skin comfortably in front of an audience, let alone by myself.”

Upon moving to Tennessee Mabry joined Toastmasters again; again he quit, this time after two meetings. “The fear of public speaking and exposing my thoughts and emotions was still too great.”

“We’re all going to make mistakes but the only way to succeed is to keep at it and to not be afraid to reach out for help when you need it.”

— JOHN MABRYBut the challenge of Toastmasters kept beckoning and Mabry’s third attempt was the charm. He says he finally realized the members were there to support him and help him improve—not pick apart his flaws and reject him.

“Once that clicked I had a different perspective,” he says. “It opened the floodgates and I’ve been able to make more progress both as a public speaker as well as in my sobriety over the past two years than I did in most of my previous 35 years combined.”

Mabry says the support he received in Toastmasters helped him feel confident and safe enough to share the details of his personal struggles with the wider world. He evolved into a polished and in-demand speaker. In addition to his success in the International Speech Contest and local Humorous Speech contests, he is now regularly asked to share his message with audiences at Tennessee colleges, universities, high schools and businesses. Mabry also is the host of a weekly podcast where he has interviewed national personalities about substance abuse issues.

Helping Others

Today Mabry pursues his passion of helping others overcome substance abuse issues in his work with Addiction Campuses, traveling to organizations to teach employees and supervisors how to create and maintain a drug-free working environment. He credits Toastmasters with playing a role in his recent promotion to director of outreach in the organization.

“It gave me the confidence to travel and talk about what we do as an organization and the lives we’ve been able to save,” Mabry says. “Without that I think I would have been content to work behind the scenes with little public contact. Of all the things I’ve done in my professional life, my role in this organization is the one I’m most proud of.”

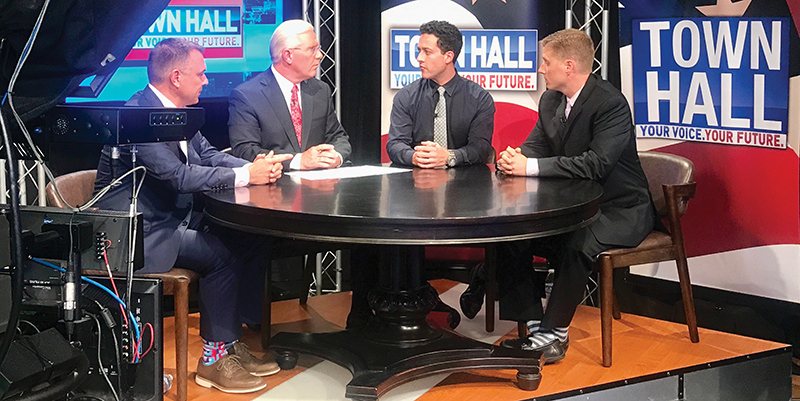

Mabry (far right) participates in a roundtable discussion of the opioid crisis that was broadcast on American TV.

Mabry (far right) participates in a roundtable discussion of the opioid crisis that was broadcast on American TV.Mabry says his time in Toastmasters also has helped him as a father and husband. “I had been scared to be a leader in my own home, for example, because I felt I was hiding from myself,” he says. “But I made a conscious decision to become a better leader for my family, and skills I learned in Toastmasters helped me communicate more effectively with my wife and children.”

The enduring message Mabry wants to leave with his children and his audiences is the importance of never giving up—and of the power of removing feelings of shame from opioid and other addictions increasingly afflicting people around the world.

“The key is to just keep showing up, whether that’s in everyday life or in Toastmasters,” Mabry says. “We’re all going to make mistakes but the only way to succeed is to keep at it and to not be afraid to reach out for help when you need it.”

He notes that addiction doesn’t discriminate against social or economic status. “No matter who you are or what resources you do or do not have, addiction is a disease that wants to kill you. You have to reach out for help from family, friends, your church, the HR manager at work, a counselor or treatment center.”

“We as a society also have to make it easier for people to ask for help by removing the stigma from opioid addiction and to treat it just as openly as any other disease,” he adds. “Only then will we start to see real change.”

Watch John Mabry’s speech “The Hero-In Solution.” His weekly podcast, “High Sobriety,” can be found on iTunes.

Dave Zielinski is a freelance writer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and a frequent contributor to the Toastmaster magazine.

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article