When COVID-19 suddenly gripped New York City in March 2020, all eyes were on its overwhelmed hospitals. Inside a Brooklyn emergency room serving one of the most impacted neighborhoods, beds with critically ill patients cascaded into the hallways. Still more were lined up on stretchers waiting to be admitted.

Many staff were out sick and there was a shortage of equipment to protect those still able to work, like Dr. Shlomo Noskow, an emergency room physician who rationed his only N95 mask to make it last for days at a time. In respites at home between 12-hour shifts of what Noskow describes as “constant damage control” and extraordinary loss, he did what many across the world also did: He thought about unfinished goals.

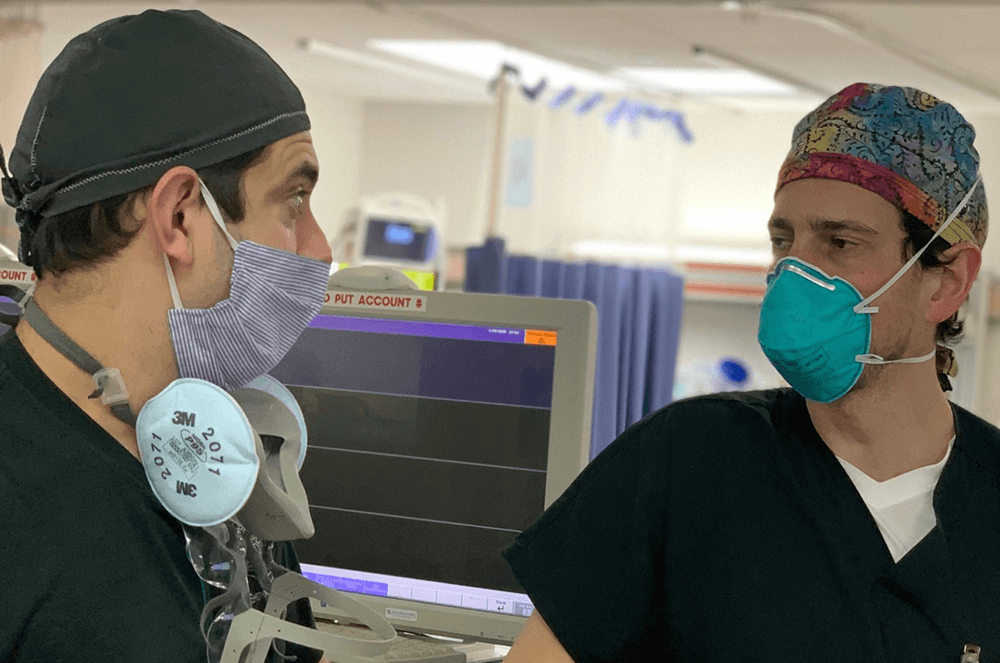

Dr. Shlomo Noskow (right) and a resident.

Dr. Shlomo Noskow (right) and a resident.As the nightly “clappy hour” of grateful New Yorkers thanking health-care workers began to wane in June, Noskow was hearing applause in a new form, over Zoom, and for a new reason: He had become a Toastmaster.

“Toastmasters was one of those things I’d been meaning to get serious about,” says Noskow, an advocate for education reform in his free time. “I want to be able to speak more confidently, more spontaneously, and just be able to be more fluid and more polished.”

Click play to hear an exclusive podcast interview with Dr. Shlomo Noskow and the hosts of The Toastmasters Podcast.

Noskow, a member of Long Island University-Brooklyn Toastmasters, is part of a small contingent of Toastmasters working in medicine. Globally, about 5% of Toastmasters members report working in the health-care field. With such demanding and important professions, how can doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals benefit from Toastmasters? In many ways, as it turns out.

“I wanted to be able to speak more confidently, more spontaneously, and just be able to be more fluid and more polished.”

—Dr. Shlomo NoskowThe following Toastmasters demonstrate that lessons learned from delivering speeches and volunteering for leadership and mentorship roles have not only made them better in their jobs—but more aspirational individuals overall. From earning additional degrees and advancing policy change to pursuing second-act careers and passion projects, Toastmasters could be the best-kept secret in the proverbial medicine cabinet.

Critical Communication

Studies show that poor communication in medical care is the single biggest contributor to unnecessary errors, deaths, and lawsuits. Something as simple as mishearing similar-sounding medications or assuming an acronym is universally understood can have critical repercussions. Noskow says this was an oft-repeated lesson in medical school.

Being clear and concise and delivering a distinct and memorable point are hallmarks of the Toastmasters program. But Noskow says the biggest difference that Toastmasters has made in his job is that he has become a better listener.

“We have to try to connect with a patient really quickly and that’s a skill if you can listen to what they’re saying. That’s something we do in Toastmasters,” he says, noting this is especially true with practice via Table Topics® and speech evaluations.

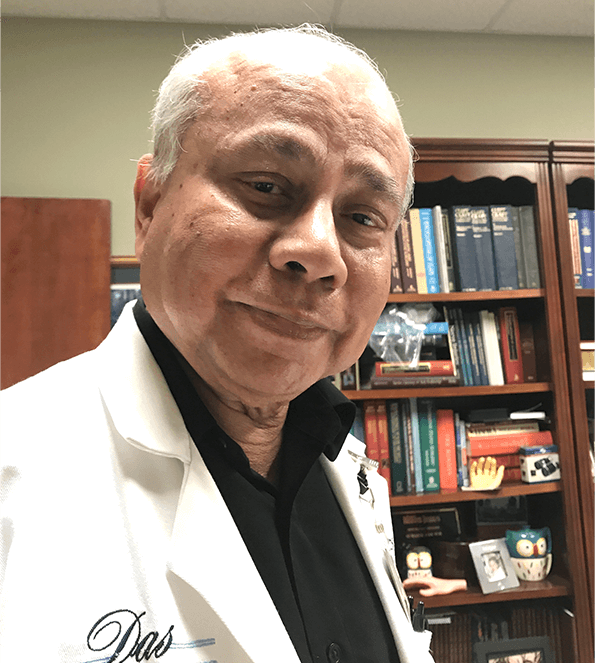

Table Topics inspired Dr. Suman Das, DTM, to join Toastmasters in 2015. A fellow physician and Toastmaster invited Das to a club meeting; he joined the next week. Das, who retired this year after 36 years as a plastic surgeon, also found that his ability to listen was enhanced by his Toastmasters training.

Dr. Suman Das, DTM

Dr. Suman Das, DTM“Many people have a habit of interrupting. They won’t let other people finish. They interject. For me, it is so important to listen to my patients. To not interrupt when he or she is giving information. And that’s an art,” says Das, a member of Reaching Beyond Advanced Toastmasters, in Jackson, Mississippi.

Das’ medical career has spanned five countries and included a decade as a medical school professor. If he had found Toastmasters earlier, he says, he would have been a more effective lecturer, pausing more in his delivery and relying less on slides. This desire to teach and influence young people led him to design and execute a High Performance Leadership project in early 2020 to teach local high school students the mechanics of good speeches.

A Story to Tell

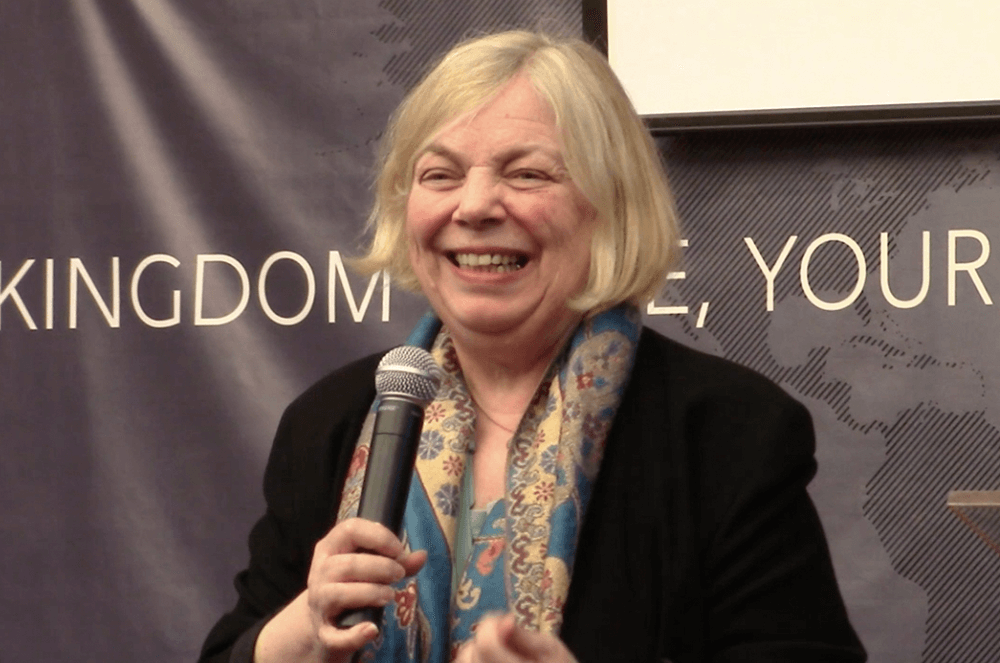

Cynthia Long, Ph.D., a pediatric surgical nurse in St. Petersburg, Florida, had already been a volunteer grief counselor for several years following the death of her husband when she sought out a Toastmasters club in 2014 to sharpen her storytelling. Within six months of joining, she had finished her first 10 speeches and felt called to further pursue her growing interest in communications. She soon found herself back in the classroom after 22 years away.

Cynthia Long, Ph.D.

Cynthia Long, Ph.D.In December 2020, she earned her Ph.D. in communications with a focus on end-of-life dialogue. Toastmasters not only gave her an edge in the classroom, where professors noticed her comfort with public speaking, but her research gave Long an endless supply of speech topics.

Long accomplished this while continuing to serve as a club leader for St. Pete Beach Toastmasters and serving as a clinical leader in the operating room, where she cares for her hospital’s youngest plastic surgery patients being treated for anything from cleft palates to jaw reconstructions.

“Toastmasters really develops you, not just in your public speaking but as a person. It develops your philosophies and passions and ideas. You’re able to formulate this to an audience because you’ve thought about these things and you’ve spoken about these things,” Long says. “It‘s a hugely profound way to get to know yourself. No therapist could ever help me as much as Toastmasters has.”

Noskow, the New York doctor, is also hoping to use storytelling to help others. A product of ultra-Orthodox Jewish schools in Brooklyn and Israel, he had little exposure to anything but strict religious studies after age 12. By 21, with limited knowledge of classroom math, science, or English, he found he lacked marketable skills for employment. He credits a love of learning, intense determination, and a subscription to The Economist for his remarkable ascension up the already steep path to becoming a physician.

"Toastmasters really develops you, not just in your public speaking but as a person. It develops your philosophies and passions and ideas."

—Cynthia Long, Ph.D.His ultimate goal now is to be a more effective advocate and eliminate for others the educational handicaps he experienced. Among the specialized speaking acumen he hopes to develop are podcast appearances, panel discussions, and press conferences, all of which also happen to be Pathways speech projects.

Making the Time

Many Toastmasters find it difficult to carve out time to dedicate to local clubs. Health-care workers have the additional challenge of unpredictable schedules, depending on their specific medical field. Noskow says Toastmasters has been an easy fit since emergency medicine has more flexibility and he can ensure he doesn’t have conflicts with club meetings. The current online format has been especially convenient, he says.

“I’ve seen how well spoken and experienced members of my club are and it makes me want to stick with it. Everyone’s been so helpful, I’m learning so much,” Noskow says. “I can tell I’m just so much more comfortable speaking freely. I’m less self-conscious.”

Das, the doctor from Mississippi, was so determined to earn his Distinguished Toastmaster award that he was a member of three clubs at one point and would wake before dawn to prepare his speeches. His next goal, besides earning his second DTM this year, is to try stand-up comedy. A local bar has promised him mic time when public gatherings are safe again. In the meantime, he serves as club Jokemaster and is working through the Engaging Humor path in Pathways. This year, he also starts a term as president of the Rotary Club of North Jackson, Mississippi, greatly expanding his stage as a speaker.

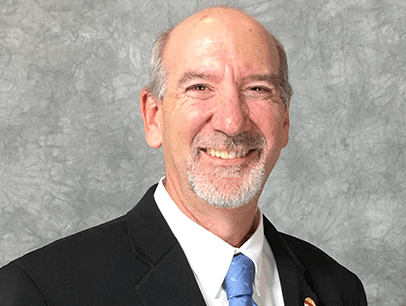

Deva-Marie Beck, DTM, Ph.D., of Quebec, Canada, came to Toastmasters as an established keynote speaker and nursing advocate. After working for 30 years as a critical care nurse in the United States, she founded the Nightingale Initiative for Global Health in 2006. The organization is a health and nurse advocacy group furthering the work of one of the most famous nurses in history, Florence Nightingale of England. In 2013, Beck befriended Wayne Kines, DTM, a longtime Toastmaster responsible for chartering over 20 clubs in northern New York and eastern Ontario, Canada. The two eventually married and Toastmasters became a shared pursuit.

Deva-Marie Beck, DTM, Ph.D.

Deva-Marie Beck, DTM, Ph.D.Beck has spoken around the world to groups as large as 3,000. Her focus is on developing others into great presenters and leaders, both through Toastmasters and her health advocacy work.

“You get to a level where you want to mentor protégés rather than be mentored yourself,” she says. “People struggling to give their Ice Breaker can have fantastic breakthroughs. To see them become people they didn’t realize they were meant to be—it’s really wonderful to be able to do that.”

Global Impact

Through her work, Beck urges nurses to be more informed, active citizens and to use their unique roles to create local, national, and international sustainable development change as designated by the United Nations. Nurses are especially key because they are consistently ranked the most trusted profession. Doctors aren’t far behind.

The pandemic has pulled back the metaphorical curtain on health-care workers. Health professionals have become prime-time and front-page media figures, leading press conferences, being quoted in the news, and rightfully taking a seat at the table to contribute to discussions about COVID-19, as well as public health, mental health, and health-care delivery disparities. Nurses’ faces have gone global on social media and their shortage has put a spotlight on the profession.

So why aren’t more health-care professionals taking part in Toastmasters? Long, the Florida nurse, believes that people commit to the things they feel most comfortable with, and getting better as a speaker means actively courting discomfort. Reputations may also play a part. Beck, the Canadian Toastmaster, says nurses are typically, by nature, introverts who entered the profession because it is usually one-on-one work with patients. And doctors, who are considered experts in their field, sometimes may balk at admitting they have room for improvement. Beck is undeterred. As the world begins to open up again after the pandemic, she plans to focus her efforts on nursing students and harnessing their social media acumen to transform themselves into global health advocates. Encouraging them to become Toastmasters will be a part of her mission to put nurses front and center.

“We are definitely a silo. We interact with each other from one shift to the next. All the way up to the global level, we usually only speak to each other,” Beck says. “We don’t speak to the world—yet. And what we have to say is pretty important.”

Emily Sachs, DTM is a freelance writer in Brooklyn, New York. She is the Immediate Past District 119 Director and is a regular contributor to the Toastmaster magazine.

Related Articles

Communication

An Impressive Operation

Member Moment

A Nurse with the Healing Power of Humor

Profile

Leading the Way in Public Health

Personal Growth