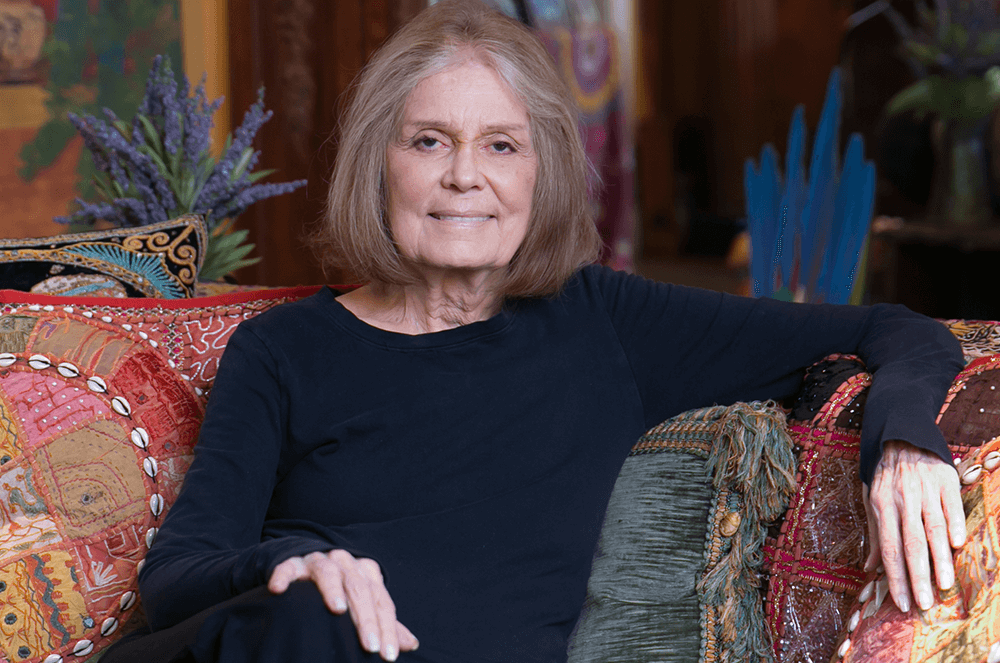

For well over 50 years, Gloria Steinem has fought persistently and passionately for women’s rights. And that has meant doing a lot of public speaking.

As an author and activist, the 90-year-old feminist icon has spoken at conferences, hearings, street rallies, sit-ins, political gatherings, community meetings, college campuses, and many other places and events through the years. But when she first started out, Steinem was terrified of public speaking.

She did it anyway—and learned something vital in the process.

“I discovered that I didn’t die. This was very important,” she says with a chuckle during a recent telephone interview.

This was in the late 1960s. As a founding editor and columnist for New York magazine, Steinem had been invited to give speeches and make media appearances, but she consistently declined. Her fear, in fact, was longstanding. She once wrote of public speaking, “I spent most of my 20s and early 30s avoiding it.”

Finally, the urgency of the women’s movement compelled her to speak. As she continued to deliver speeches, she slowly grew more comfortable.

“I became a writer partly so I didn’t have to talk,” she notes. “It’s not my most natural form of communication, but once I stopped thinking of it as public speaking and thought of it as a conversation with individuals, even if they were in an audience, it helped.”

She wanted her speaking to be an act of facilitation, sparking audience members to discuss issues and ask each other questions. She called this a “talking circle.”

“So the time of speaking at the beginning [of the program] becomes mainly something that is shared for people to respond to,” she explains. “But the interesting time is the discussion.”

Photo Credit: Beowulf Sheehan

Photo Credit: Beowulf Sheehan As her journey continued, Steinem became a cultural fixture. In 1971, she co-founded Ms. Magazine, the first feminist publication with a national readership. A familiar sight in her hip clothing and oversized glasses, Steinem gave voice to women who wanted change. She spoke out against discrimination and societal constraints, and advocated for women’s empowerment, including equal opportunities and pay.

Starting out, she found comfort and courage in teaming up with friends for speaking appearances. Her speaking partners included Dorothy Pitman Hughes, a pioneer of multiracial childcare in New York City, and Florynce Kennedy, a bold and charismatic civil rights lawyer. Steinem, author of the 1983 book Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions, says she learned a great deal from these self-assured women.

“It’s not my most natural form of communication, but once I stopped thinking of it as public speaking and thought of it as a conversation with individuals, even if they were in an audience, it helped.”

–Gloria SteinemKennedy taught her to use stories, not statistics, to make powerful points about discrimination. Kennedy also showed her how to handle hostile audience members. While she was revered by many, Steinem, especially in her early years of activism, drew the ire of men (and some women) who preached the virtue of the status quo and resented “women’s libbers.”

In 1971, Steinem spoke at the annual Harvard Law School banquet. At the time, women accounted for 7% of its students, she said, and the faculty was composed entirely of white men. Her speech criticized the law school’s treatment of women. Among her comments: “Politics don’t begin in Washington. They begin with those who are oppressed right here.”

Afterward, a Harvard Law professor in a tuxedo rose from his table and angrily ripped into Steinem, berating her for daring to pass judgement on the venerable school. A law student in attendance later wrote that the professor’s boorish behavior made Steinem’s argument for her.

Which is why she came to appreciate the speaking advice Kennedy once gave her for such occasions: “‘Just pause, let the audience absorb the hostility, then say, ‘I didn’t pay him to say that,’” Steinem recalled in My Life on the Road (2015).

At other times, she dealt disarmingly with men asking about her sexual preferences. “If someone called me a lesbian—in those days all single feminists were assumed to be lesbians—I learned just to say, ‘Thank you,’” she wrote in the same book. “It disclosed nothing, confused the accuser, conveyed solidarity with women who were lesbians, and made the audience laugh.”

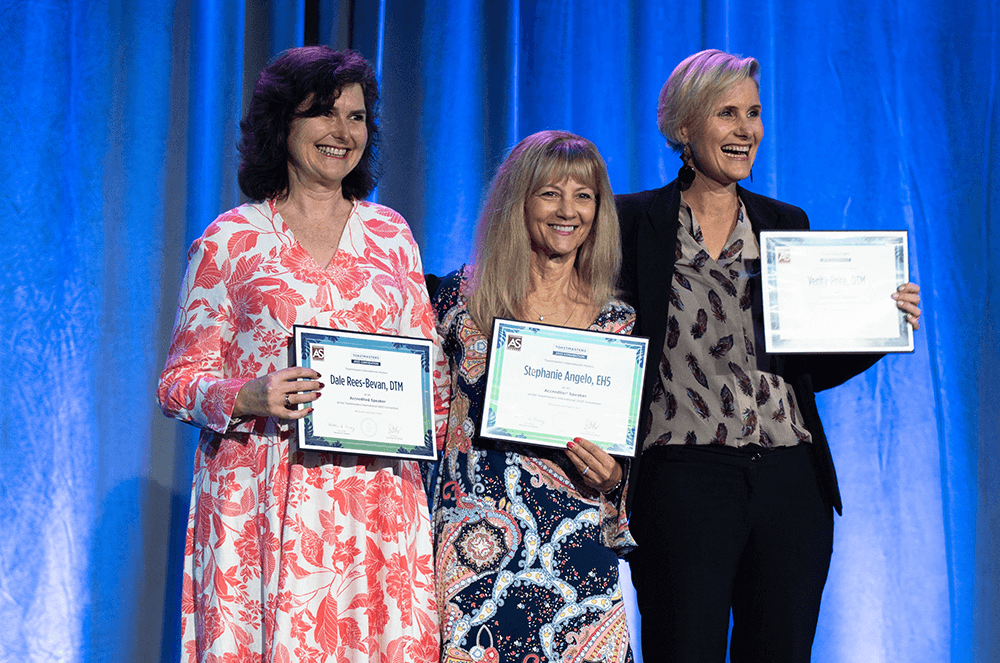

Photo Credit: Kamila Harris

Photo Credit: Kamila HarrisSomething Steinem also emphasizes is the value of listening. She is at heart a journalist and has always made it a point, for example, to interview students before speaking on college campuses, and to seek out many people and perspectives during her travels inside and outside of America.

“You don’t learn nearly as much by sitting in your office as you do going out on the road,” she says, “and doing it in an ‘on the road’ state of mind—that is, listening and paying attention, whether it’s somebody in the gas station, or someone in the airport.

“It’s an adventure. It’s a way of learning.”

As time has passed, Steinem has become a towering figure in the world of civil rights. She has spoken out on many issues beyond the women’s movement, advocating for racial and economic equality and LGBT rights, as well as various social and political causes. A longtime New York City resident, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by former United States President Barack Obama in 2013, and in 2019, received the Freedom Award from the National Civil Rights Museum.

Steinem gave voice to women who wanted change. She spoke out against discrimination and societal constraints, and advocated for women’s empowerment, including equal opportunities and pay.

But Steinem isn’t much one for looking back and basking in accolades. Asked if she feels a sense of satisfaction with her life’s work fighting discrimination, she replies, “Well, yes and no. I certainly feel amazed and gratified by the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, the gay and lesbian movement … but, of course, I’m not satisfied.”

She can’t be, she says, until “we’re each regarded as a unique individual without adjectives.”

Paul Sterman is senior editor, executive and editorial content, for Toastmasters International. Reach him at psterman@toastmasters.org.

Related Articles

Presentation Skills

When Women Speak—Listen

Toastmasters News

Three New Accredited Speakers Emerge

Toastmasters News

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article